19 February 2016, Reuters Investigate

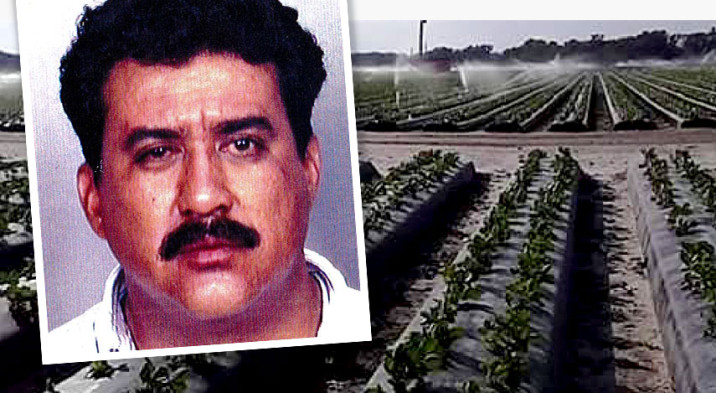

Nestor Molina has made a living looking for Honduran workers to pick fruit in Florida. Now, some of the workers he recruited, their lawyers, and the U.S. government are looking for him.

Molina, 53, is among the middlemen hired by companies to help bring foreign workers to the United States for temporary jobs.

The jobs span almost every industry, from agriculture to hospitality, and the numbers of foreign workers brought to the United States have swelled in the past two decades. In the fiscal year ending last August, the government issued more than 350,000 temporary work visas.

Public attention has focused largely on U.S. employers that exploit foreign workers. But Reuters identified an insidious problem that precedes and can compound the abuses workers face when they arrive in America – and one that authorities say can be even more difficult to address.

In more than 200 civil and criminal cases Reuters examined that were filed in federal court, lawyers representing the government and tens of thousands of foreign workers allege myriad misdeeds committed by middlemen such as Molina – labor brokers enlisted by U.S. companies to navigate government bureaucracy, recruit workers, help secure visas, and arrange transportation for those who are hired.

The alleged transgressions range from wage theft to human trafficking. Molina has been accused in a lawsuit by a group of Honduran migrant workers of charging them thousands of dollars apiece in illegal recruitment fees, among other abuses. U.S. authorities told Reuters they are investigating the allegations against Molina, whose whereabouts are unknown and who couldn’t be reached for comment.

One non-profit group that counsels American corporations on labor matters warns its clients that hiring intermediaries to recruit workers increases the likelihood of illicit activity within labor networks. In part, that’s because the brokers operate as independent contractors, essentially answering to no one.

“These brokers are outside anyone’s control,” said Quinn Kepes, a program director at the non-profit group Verite.

Anna Park, an attorney with the federal Equal Employment Opportunity Commission who has brought civil cases against brokers and employers on behalf of foreign workers, said the middlemen are hard to hold accountable if workers are exploited.

“These companies are fly-by-night. They are able to secure legitimate visas and operate within the system,” Park said. “When their practices are scrutinized, they often disappear and reinvent as a new company.”

The cases that Reuters examined dated from 2005 to 2015 and describe alleged abuses by labor brokers that began outside America’s borders – in Mexico, India, the Philippines and other countries where brokers recruit.

The cases illustrate how the absence of government oversight has allegedly enabled some brokers to exploit workers – and how intermediaries can insulate U.S. companies, providing them plausible deniability about the circumstances under which workers were recruited.